There are dog owners who are positive they know exactly what their dogs are thinking, and they are the ones who tend to anthropomorphize and project their own thoughts upon the dog. Say this dog owner is named Betty. My guess is that much of the time Betty is right, but probably not to the extent that she supposes. Scientists have recently been able to do advanced experiments to get a better sense of what the dog’s mind is capable of thinking. It was two books by Dr. Gregory Berns that got me started learning about what neuroscience and behavioral analyses could tell us about our favorite companions.

A dog’s brain is about the size of a lemon with about 5 billion neurons vs. the 80 billion we have. The olfactory bulb, ~ 10% of the dog’s total brain, helps them process smells. It is absent in humans and, not surprisingly, dogs’ sense of smell is 100,000 times more acute than that of a human. On the other hand, the frontal lobes in the dog, the thinking part of the brain, are also about 10% of the volume, so dogs have evolved with the same brain capacity for processing scent and for thinking. The frontal lobes in humans are 30% of their total brain. Just knowing that means dogs must perceive the world differently than we do.

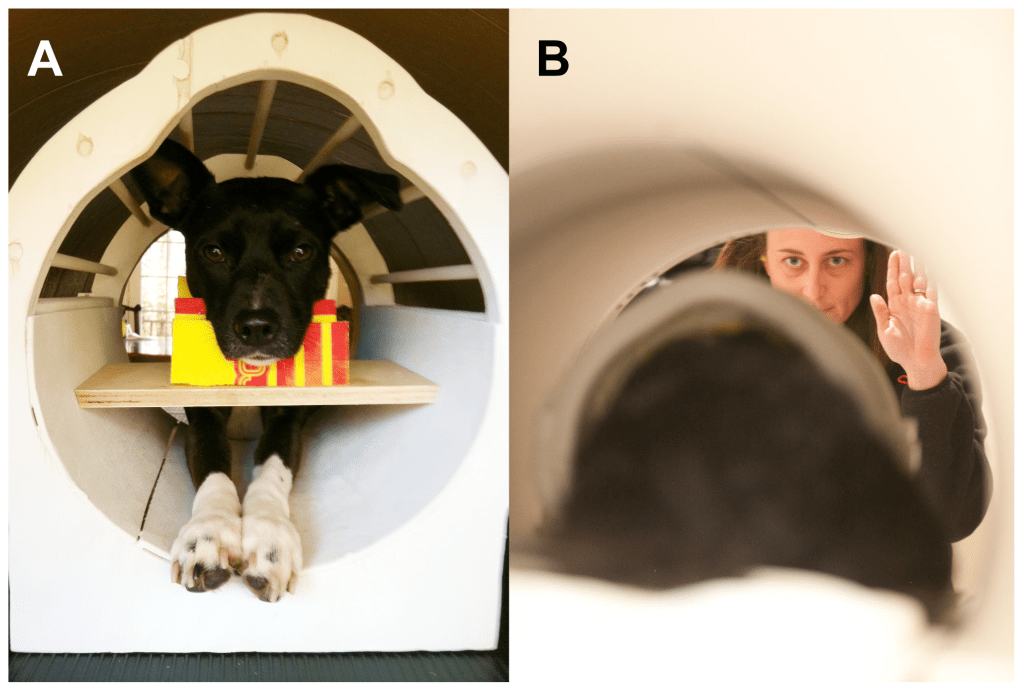

Dr. Berns uses fMRI brain imaging to ask his questions. The “f” stands for functional, MRI is “magnetic resonance imaging” and, using huge, clanking magnets, he can measure the areas that are most active in the brains of awake subjects. When nerve cells are working, they have high energy needs and cause a localized increase in blood flow to get the nutrients and oxygen to where it is needed. fMRI measures those blood flow changes. This technique has revolutionized neuroscience research for humans, as it allows scientists to see what parts of human brains turn on when we think about different things. It is much trickier to do these experiments in dogs, and that is where some of the beauty of Dr. Berns’ work comes in. He and other volunteers trained their dogs to keep their heads completely still (movement destroys the images), and to do so in the confined and noisy environment of the fMRI.

Cool fMRI Experiments in Awake Dogs

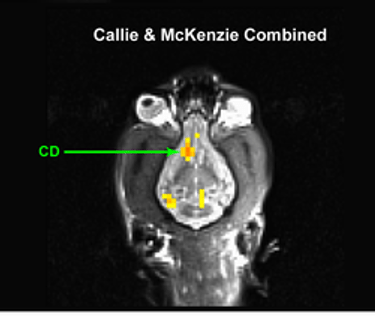

Dr. Berns and his colleagues devised clever ways to test what dogs were thinking with the use of previous training, hand signals and sensory stimuli, while the dogs kept immobile for the moments needed to capture the signal. Their first simple experiments took months to complete because they had to figure everything out from scratch. If you are interested in the details, I highly recommend reading his first book. They trained the dogs that one hand signal meant a delicious treat was coming (anticipation of a reward) and the other meant nothing interesting would happen. The dog brains showed activation in the fMRI in a region called the caudate nucleus with the anticipation hand signal, already known to be the reward center in humans. Activation of our caudate nucleus is linked to desire and craving, becoming dysfunctional in addiction. So when my dog Henry danced around anticipating the dinner I was preparing for him, he was actually anticipating that meal with pleasure like I thought he was.

In another set of experiments, Dr. Berns and his colleagues exposed the dogs to cotton swabs with sweat from their owner, an unknown human, or from the anal glands of themselves, known or unknown dogs. This allowed measurements from a sensory system they preferred, and it was no surprise to see the olfactory bulbs light up in the fMRI with all tested odors. What was most interesting was the dog brain’s response to the scent of their owner’s sweat. It also lit up the caudate nucleus (Yes, you remember, it’s anticipation and reward), as well as the inferior temporal lobe associated with memory functions. The owner was not present, so the fMRI signals told us that the dogs remembered the owner as special and distinct. “These patterns of brain activation look strikingly similar to those observed when humans are shown pictures of people they love.” So when our friend Betty believes her dog loves her as much as she does, this may be true. Or it may be a variation on the theme, but something special is definitely happening.

Also, dog owners often refer to their pets as their dog-babies, and many young couples will get a puppy before committing to parenthood to try out the idea of caring for another being. Behavioral scientists determined that the dog-human attachment style was similar to the infant-caregiver style and that the dog-dog attachment style was more like a sibling interaction, once again validating what many dog lovers instinctively feel. In addition, jealousy of human attention to another dog has been recorded in the scientific literature, just like siblings.

My mother always said that living with a dog was like living with a perpetual toddler, and I have found that to be true as well! One of the studies Dr. Berns conducted was on impulse control. In What It’s Like To Be A Dog, he showed that dogs do have some impulse control but that it varies a lot between individuals, just like in humans. The level of fMRI activity in the prefrontal cortex of the dogs correlated with each dog’s result from an independent test of impulse control. In humans the prefrontal cortex is involved in executive decisions and self-control and is an area not well developed in small children. Based on their overall performance… yes, dogs are permanent toddlers in the home.

Dogs and Human Language

One of the most fascinating parts of that book was Dr. Berns’ investigation of language comprehension. There are a few famous border collies who have been documented to understand the names of hundreds of different words when asked to retrieve specific objects. Chaser probably holds the record with 1022 words and even some noun-verb pairings. His owner, John Pilley, trained and played with him for 4-5 hours a day, which was surely related to this dog’s phenomenal success, but it couldn’t have happened without Chaser’s innate intelligence.

We’ve tried to teach our Standard Poodle toy names and been surprised at how difficult it has been to get beyond the name of a few favorites. According to one measure of dog breed intelligence, poodles are number 2—right behind border collies—so what is going on? It turns out that Berns and his volunteers were also frustrated. They had troubles teaching recognition of just 2 objects to their dogs, to the point where the dogs still made lots of mistakes after 6 months of training. When they were finally imaged for language recognition, Berns used those two words along with some nonsense words. The nonsense words activated the brain the most, indicating that the dogs knew they were different and they should pay attention. But the known words, after all that training, were not lighting up the auditory or visual cortex in the same way that humans do after they hear a word they recognize. Our fMRI signals show that we can imagine it in our mind’s eye. This means that dogs do not understand language the same way we do and the old Gary Larson “What Dogs Hear” cartoon is probably pretty accurate. Sorry, Betty.

But dogs do have their own intelligence which is exquisitely tuned in to human behavior, and so Dr. Berns thinks about the question of language in a new way. Humans like to name everything. Sight is our primary sense and from the youngest age we are taught what different objects are. There are ten times more nouns than verbs in the English language. But what if dogs have an action-based, rather than an object-based world view?

“In an action-based worldview, everything would be transactional. Even emotions might be represented as actions. Fear would become that feeling in which I need to get away from something. Loneliness would be that feeling which is lessened by waiting by the door until it opens and then goes away.

“I am not just anthropomorphizing. The words I used were a necessary construct of communicating an idea in written form. A dog could not think the literal words I wrote, because the dog doesn’t have the brain architecture for thinking in words. An action-based semantic system does not mean, however, that fear is just the set of motor programs that an animal implements to escape something unpleasant. The motoric aspects are important, but so is the subjective awareness of what’s happening, for that is where we have common ground.”

If we really want to understand what our dogs are thinking, maybe it means we need to twist our thinking a little to get into their point of view. Perhaps what my Henry was really hearing was Blah Blah Blah Go Out Henry, Blah Blah Henry, Blah blah Eat blah blah.

Key references:

How Dogs Love Us: A Neuroscientist And His Adopted Dog Decode The Canine Brain by Gregory Berns

What It’s Like to Be a Dog: And Other Adventures in Animal Neuroscience by Gregory Berns

Donna Barten is a novelist and scientist working on her second book Imprint and Inheritance. Henry, her beloved companion passed on before this blog was published.