And Thank You For Asking- It’s a Long Game

I just finished my second novel, Imprint and Inheritance. It’s hard to say “finished” when I’ve been intensely writing and editing it for about four years, and at some point in the future it will surely be edited again before any of you see it. But it’s finished to my satisfaction. For now. I’ve shared it with four beta readers and a sensitivity reader, edited it again, and now sent a query package to the first round of eight agents. I’ll keep sending it out until I find an agent, and then they will do a similar thing until they sell it to a traditional publishing house . . . at least that is the dream.

An agent’s job isn’t easy. They spend most of their time promoting the clients they have, then on their “free time”, they go through the queries they get from new authors. Also included in their free time is reading requested manuscripts, and reading in general, which is the pleasure that usually gets them into the business. Agents typically get 100 queries per week. They’ll request to see a full manuscript 1% of the time, often less. An established agent will sign on, maybe, one new client per year. That’s why we writers have to spend so much time querying. There are a lot of stories out there with an author’s heart attached to it. Hoping.

Sounds daunting, doesn’t it? I’ve been seriously writing fiction for ten years now. It’s been fun, tedious, energizing, enervating, and something to occupy my mind as I’ve continued to learn the craft of writing. I don’t regret all those hours. I’ve created a beautiful piece of work and have already started thinking about the next.

Which brings me to the second part of the title of this article. Thank you for asking. I have many friends who periodically ask how things are going with the book. I often don’t have much to update, these big milestones are few and far between. Sometimes it gets embarrassing, as if nothing is happening, but really, I’ve made steady progress and continued to work right along on it.

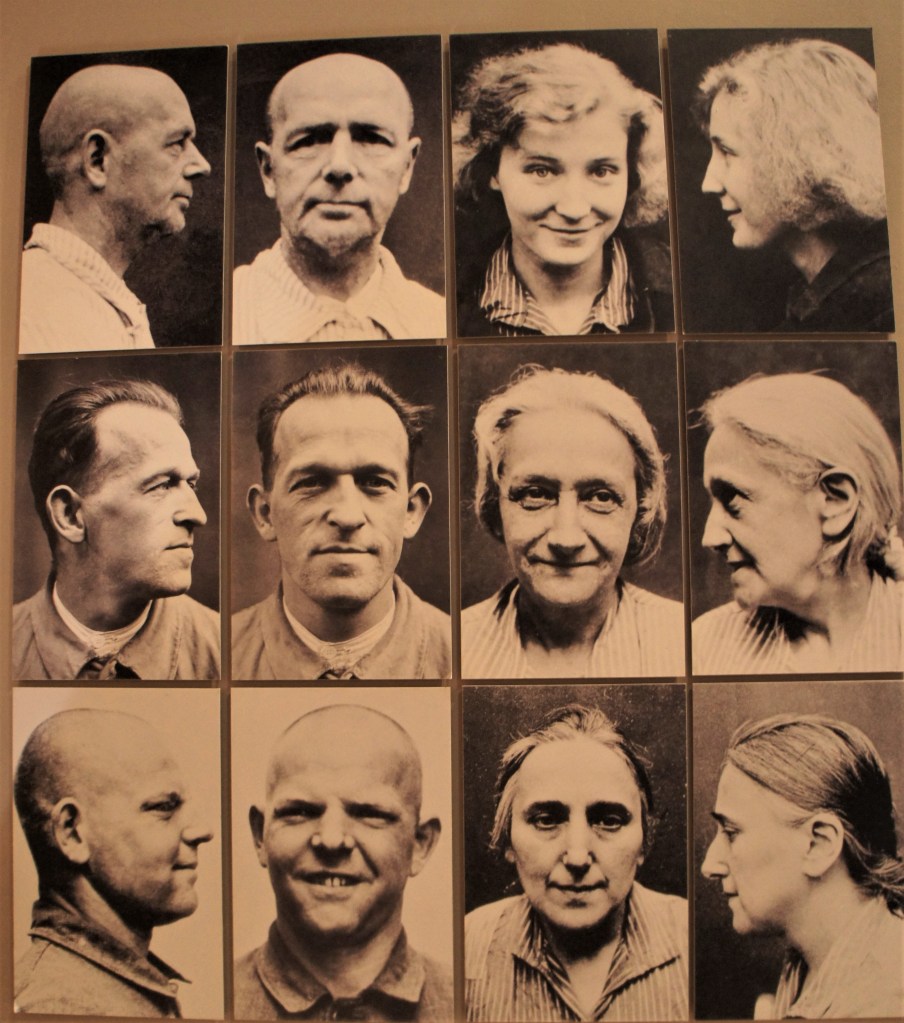

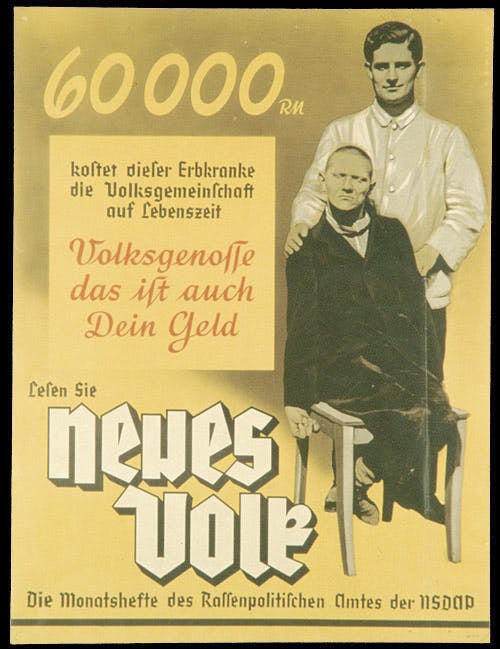

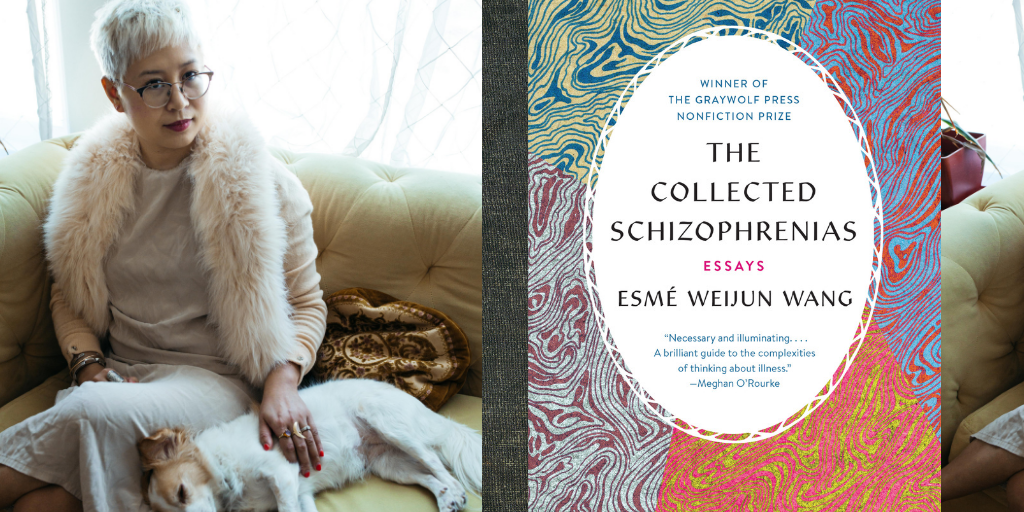

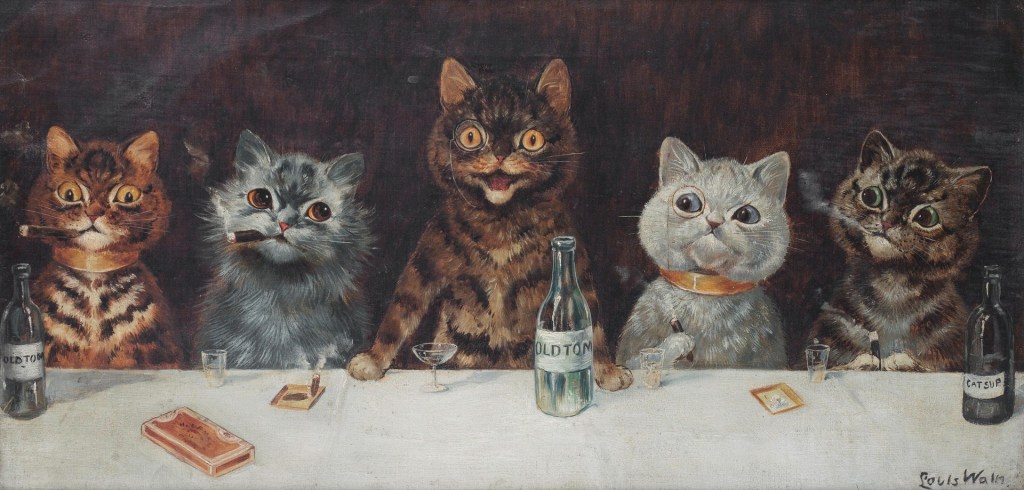

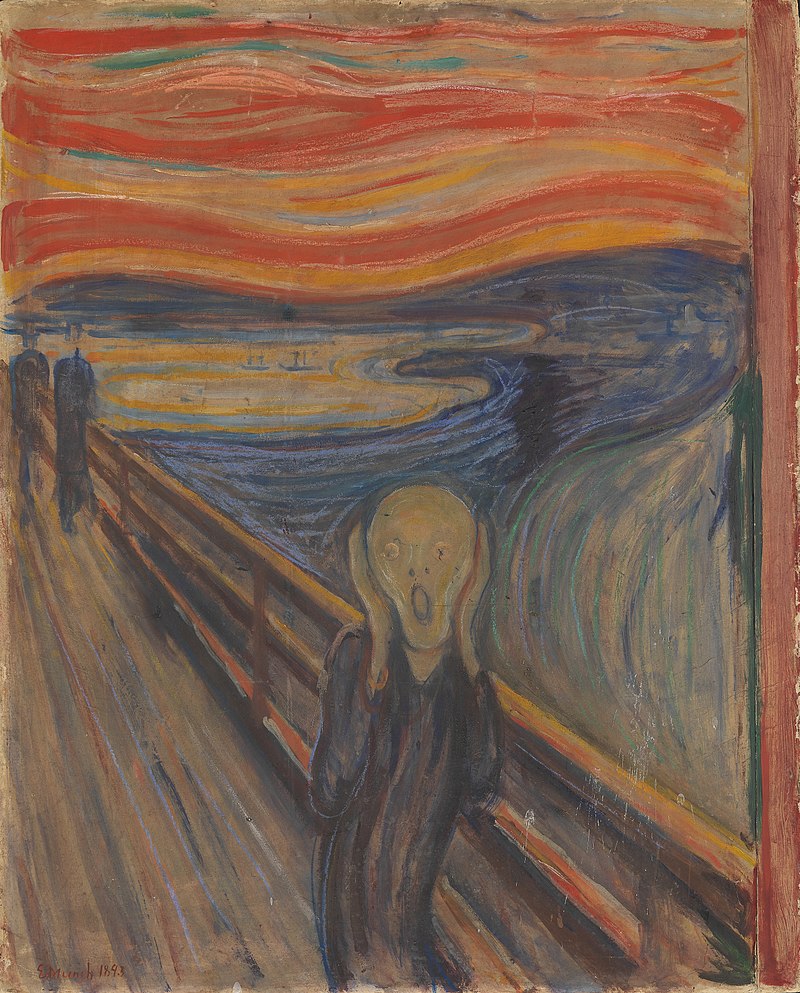

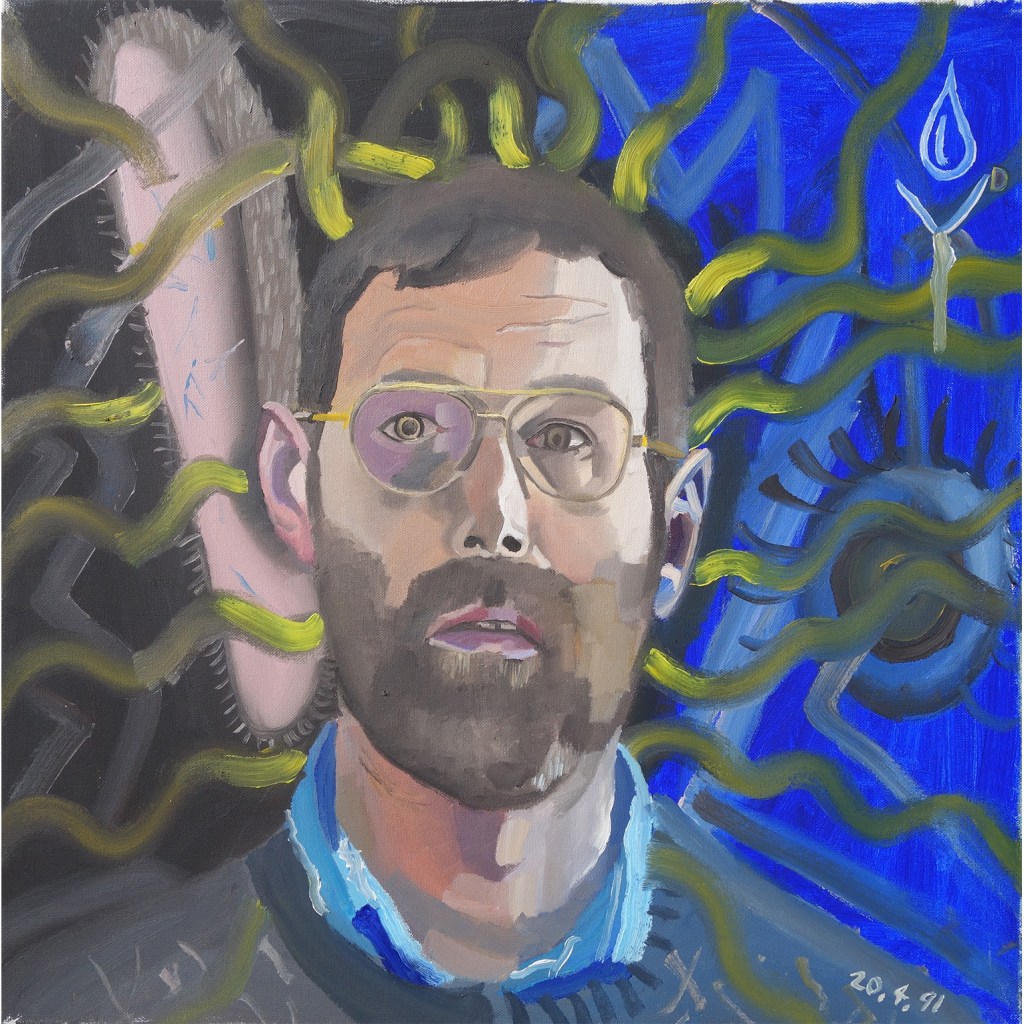

This summer, someone I barely knew asked me what the book was about. They were a neatly-dressed and composed person with a family and job and a house. I think you’ll know who you are, because that person signed up for my email newsletter right away. It happened to be at a time when I was starting to wonder if anyone would even want to read my book. It’s about a family with mental illness and alcoholism and how the trauma of growing up with all that passes through several generations. It’s about the interplay of genetics and environment and how they can create susceptibility to mental health problems, substance use disorders, and poor lifetime health. It’s how children who grow up with those things still carry a slight ache inside. Hidden. Not a light and happy topic, even though it’s also about resilience.

As I described the book, the person I spoke with just about jumped out of their chair. It was almost as if I had written the book just for them and they wanted to read it as soon as they could. You see, that person had those problems while growing up as well. I think they felt seen and understood and the pain they’d secretly lived with didn’t have to be so secret all the time.

In 2023, one in four children in the United States had a parent struggling with substance use disorder, including alcoholism. Another survey estimates that about 4% of parents had a serious mental health event in the past year. Often there are overlaps. One in five high school students surveyed experienced at least four adverse childhood events. The original ACE study in 1998 had ten categories, but I’ve just read a more recent study that looked at 55 categories of adverse events.

The higher the ACE score, the higher the risk of mental and physical disorders later in life, as you can see within the generations in Imprint and Inheritance. Those are risk factors, NOT templates for a future, and more recent studies are working on identifying and encouraging PCEs, protective childhood events, in those who need them.

Resilience is strong within the human family, but these numbers show how many seemingly ordinary adults carry little nuggets of pain from childhood. Perhaps reading Imprint and Inheritance will help them gain some perspective, including that they’re not alone in their experiences.

That conversation this summer buoyed me on. Thank you for asking.

As you can see above—it’s a long game. Growing a novel is like starting perennial flowers from seed. You must be patient. There will be no blooms the first year. You tend them and hope the plants survive the winter. Sometimes they don’t. Sometimes they need multiple years to have a display of blooms that create the vision you hoped for. This year my anenome saponica flowers begun in 2023 were finally as gorgeous as the ones I admired in Scotland and had wished for my own garden.

Wish me luck with Imprint and Inheritance; I’ve already gotten my first rejection. I hope this novel can get to the people for whom it will more than resonate. Once I find an agent (which can take a year…!), it will take at least a year, usually more, before it’s published. So, hang in there. It’s a long game and thank you for asking. Thank you for caring.