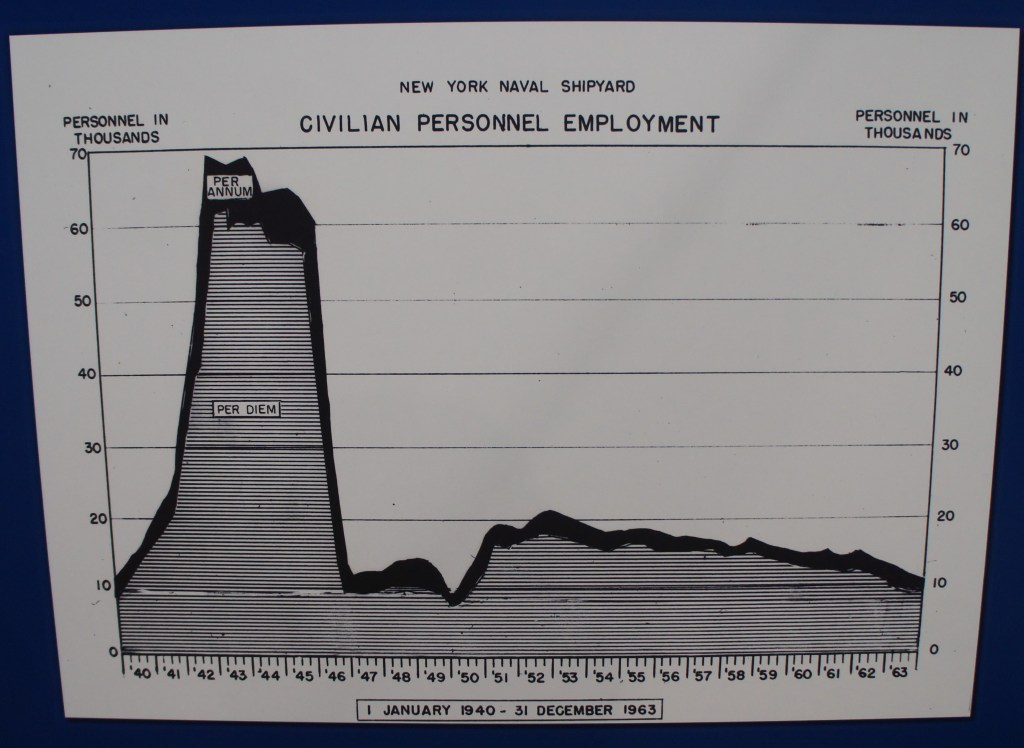

In my novel, Breathing Water, Tony’s father works at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, along with ~70,000 others during the WWII peak and ~10,000 others during peacetime. They mostly built battleships and aircraft carriers and did repairs on any number of other types of ships. The USS Arizona (sunk in Pearl Harbor) and the USS Missouri (where the peace treaty with Japan was signed) were both built there.

As ships became larger, it became trickier for them to navigate the currents of the East River and under bridges. In 1960, a disaster at the Brooklyn Navy Yard tarnished its previously stellar reputation, making it easier for the Navy to close this site as they turned to private shipyards. The Brooklyn Navy Yard was decommissioned in 1966. It’s funny that the fire at the USS Constellation is not better known, even though it played constantly on the news, as in modern day disasters, and it had such a large impact on so many people in the 1960s.

As ships became larger, it became trickier for them to navigate the currents of the East River and under bridges.

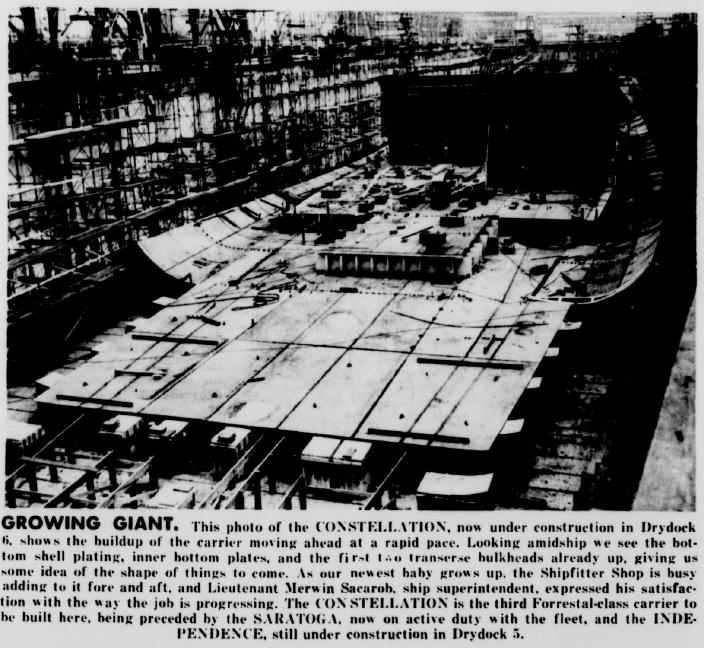

The disaster started with something very small, and then Murphy’s Law kicked in. An 1800 pound steel plate was resting on a pallet on the deck of the nearly completed USS Constellation. It would be the largest conventional aircraft carrier in the fleet and, after three years, was only a few months from completion. The ship was over 1000 feet long, or as long as 5 city blocks, and as high as a 22 story building, with room for 85 airplanes and over 4000 crew members.

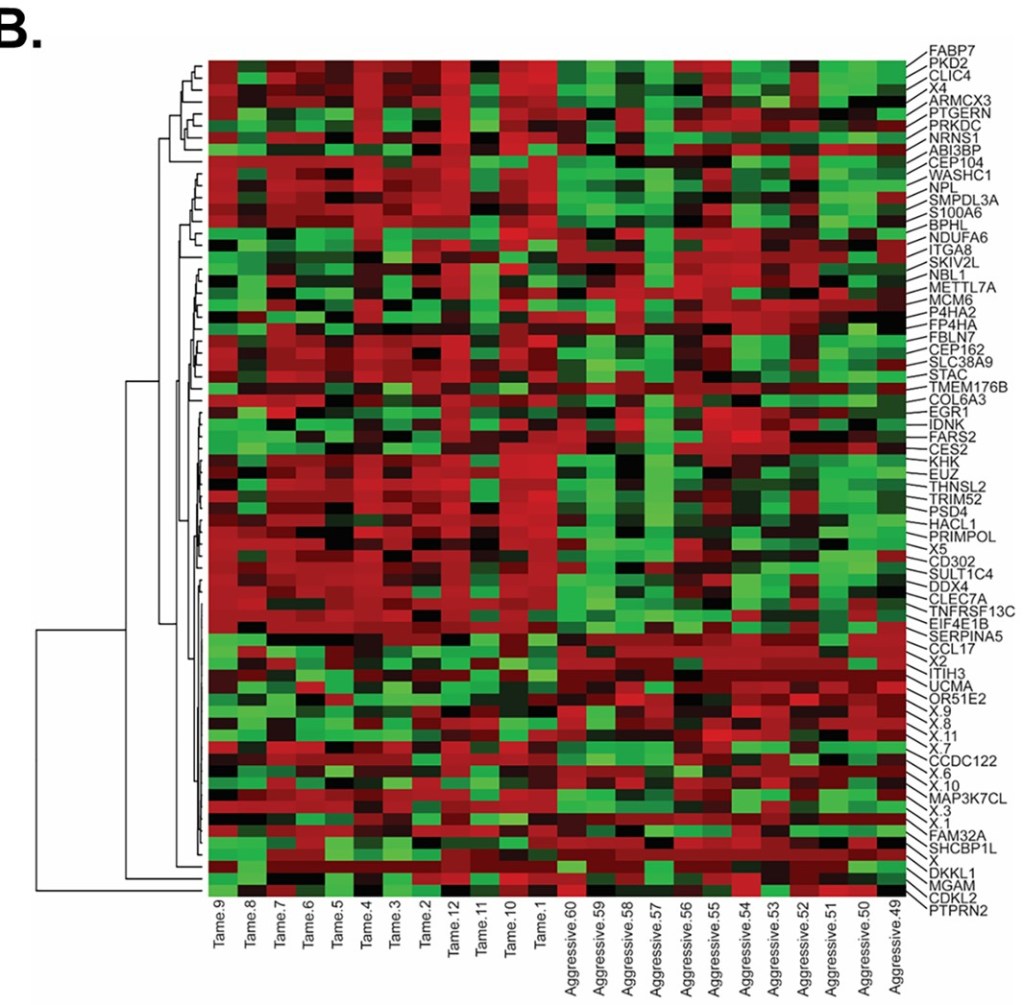

Early stages of construction in Drydock 6, The Shipworker Volume XVL#49, Dec. 6, 1957 (Left), and installation of boiler #1, The Shipworker Volume XIX#46, Dec. 9, 1960, shortly before the fire. The Shipworker collection; MC/63; Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation Archives, Brooklyn, NY.

A forklift operator moving a metal trash barrel on the deck bumped it into the metal plate. The plate shifted and knocked the spigot off a diesel fuel tank, leaking about 500 gallons of flammable liquid onto the deck. The fuel worked its way into lower decks where multiple crews were cutting and welding metal. A fire was triggered, but was not able to be quickly contained because the carrier was full of wood scaffolding and other sources of flammable liquids. When the fire grew out of control, over 3000 blue-collar workers were within the structure.

The fire department had to deal with an immense structure full of unlit, narrow passageways and they required self-contained breathing apparatuses. Beyond the extensive fire and smoke, the metal of the ship became so hot it melted the rubber on their boots and turned the hose water to steam, forcing the firefighters back. They had to wait to approach and repeat the wetting cycle until the metal was cool enough to proceed. The fire was so large that firefighters were called in from all over the City, including trainees from a nearby fire training school.

So much water was poured into the ship that it began to list to the starboard side by 4 degrees. Once it reached 5 degrees, it wouldn’t be safe for the firefighters to continue, so the decision was made to open seacocks on the port side. Enough water was let in to reduce it to a 2 degree list and thankfully no workers were harmed by doing so. To make matters worse, it was especially frigid for that time of year, at 11oF, and it began snowing during the operations, making it harder for everyone.

Rescue operations saved most of the men. They escaped by jumping onto barges or directly into the icy water, or by barricading themselves in airtight compartments, hoping someone would reach them in time. Rescuers moved along the hull listening for tapping, then cut through the 2.5 inch steel to get them out. They made creative use of ladder trucks and cranes because the ship was so tall. Oxygen, resuscitators and inhalers were in short supply as regional hospitals didn’t have enough to for all the injured. 70 pieces of equipment, 350 firefighters and 65 hoses were used to put out the fire which took 12 hours to contain and another 5 hours to completely put out. Radio and TV provided detailed reports to the City throughout the day and night as many families worried about their loved ones.

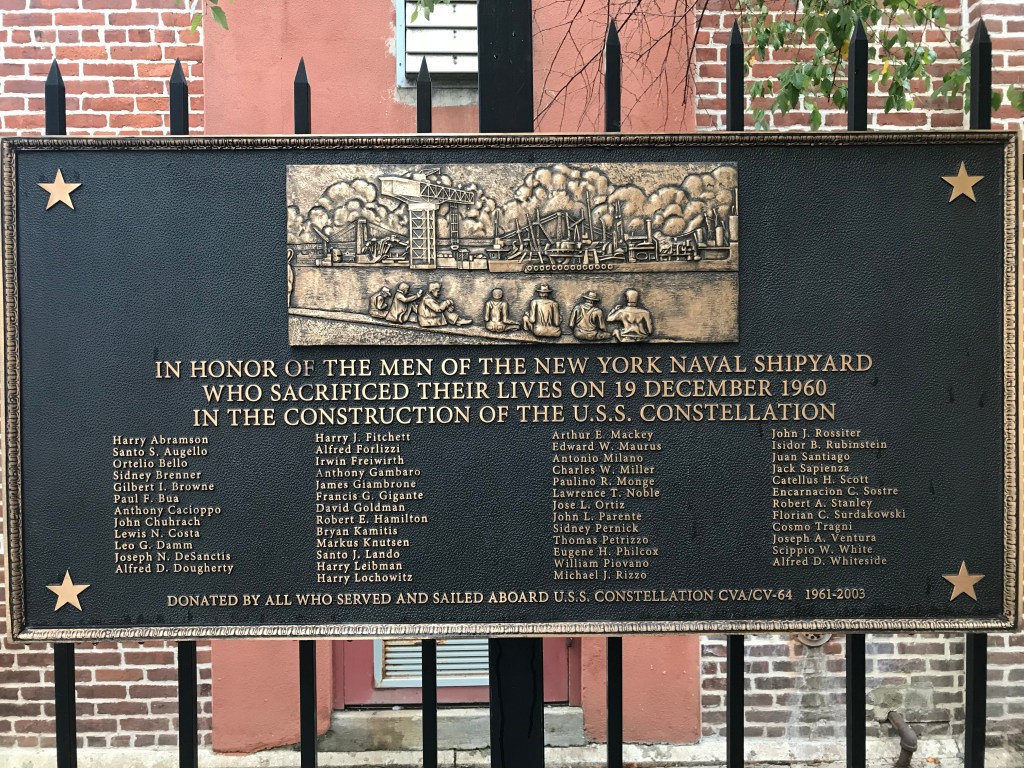

Multiple men described it as a living hell and by the end, 50 of the workers had lost their lives. Their names are commemorated on the plaque below. Another 330 employees and 40 firefighters were injured in the conflagration.

In true Murphy-style, the New York Fire Department had much more than this one disaster to deal with, as this was only the second of four very large fire/disasters they put out within a week or so. The first happened 3 days earlier and some of the men helping at the USS Constellation fire had not quite recovered from the trials of that disaster. On December 16, United flight 826 and TWA flight 266 collided in low visibility conditions over Brooklyn, with one crashing into the Park Slope neighborhood, just 2 miles away from the Navy Yard, and another into Staten Island. 128 passengers and 6 people on the ground were killed. Days after the Constellation fire, a lumber yard in Williamsburg and a gas station in Coney Island caused 8 and 4 alarm fires, respectively, taxing a weary, but dedicated NYFD. Check out this real time footage of the first two catastrophes below and this NYFD document with lots of photos and details from the Constellation.

The USS Constellation was eventually repaired and completed in October of 1961, at an additional cost of $75 million. Other fires would happen on board, but none would be as devastating as that at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. It was in service for 41 years when tens of thousands of Navy personnel walked its decks. It was in commission during the Vietnam and Gulf wars and projected American might across the world. President Ronald Reagan designated it “America’s Flagship” during a visit, but it was usually referred to as “Connie” by those who lived on it. The USS Constellation was also the site of a sit-in protest by Black sailors in 1972, protesting systemic racism within the Navy. A Disney children’s movie, Tiger Cruise, was filmed on board. After decommissioning, it was sold for scrap and disassembled in 2015-17.

The Brooklyn Navy Yard was once New York’s largest employer. During peak employment in WWII the largely white male workforce became 10% female, including as pipe-fitters, electricians, welders and sheet metal workers. Look for an upcoming article about “Rosie the Riveter” to learn more. The Navy also started employing minorities during WWII, mostly African Americans, to make up 8% of the workforce. After hostilities ended, the women all lost their jobs, but minority employment continued to inch up to 20% by the time the Yard closed.

New York City was eager to use the 300+ acre site to generate other jobs and they negotiated purchase of the site from the US government. Now the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation is a non-profit organization promoting small business development onsite, currently including 450+ businesses employing 11,000 people for a 2.5 billion dollar economic impact. Steiner Studios is the largest and most sophisticated studio complex outside of Hollywood and a wide range of other businesses thrive there. You can take a guided tour of the historic parts of the old Navy Yard today.

Donna Barten is a novelist and scientist awaiting publication of her first novel, Breathing Water.